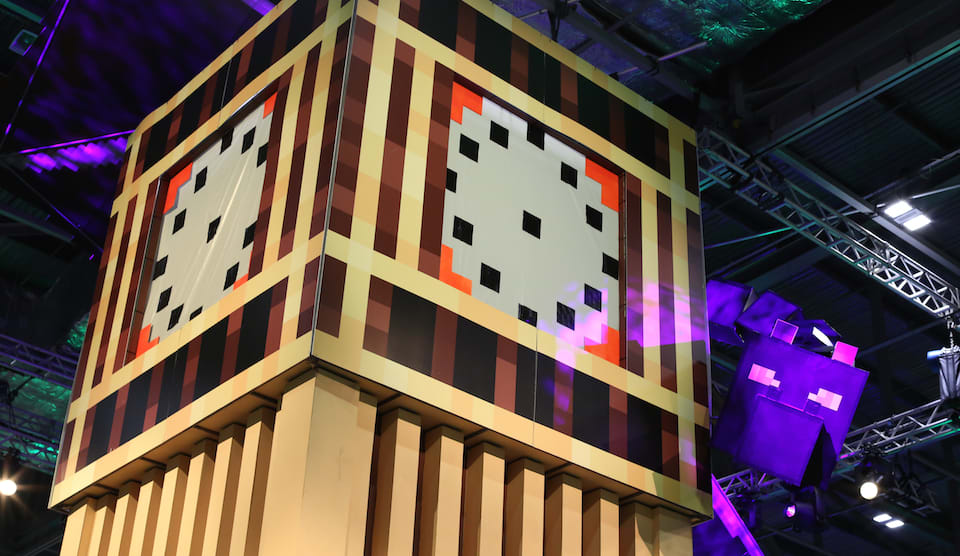

Inside the main convention hall, children scurry left and right with foam diamond swords raised high above their heads. Eyes wide and mouths agape, some of them rush toward a blocky reimagining of Big Ben, where Minecraft‘s formidable Ender Dragon can be found wrapped around the clock face. Below, parents wander between life-size character statues and trees with cube-cut canopies, a mixture of fascination and bemusement etched onto their faces. For one weekend in July, 10,000 of the most dedicated Minecraft players have descended upon London’s Excel Exhibition Centre for Minecon, a fan convention celebrating the blockbuster sandbox building game. With panels, signings, tournaments and merchandise, it’s the Minecraft equivalent of Disney World and Comic-Con.

Minecraft is an anomaly in the video game industry. The first version was released by Markus “Notch” Persson in 2009 and was quickly championed by the press and indie game community. With no marketing, the desktop version surged in popularity as players embraced the primitive, colorful aesthetic and non-linear gameplay: Build a home, survive the night and then do whatever you like. Even now, it takes time for beginners to learn how to craft different items, and the randomly generated worlds always provide a fresh challenge. The game is unique and, surprisingly, no developer to date has managed to copy the experience and its commercial success.

More than six years after its debut, the game continues to sell. Persson is no longer attached to the project and the studio he founded, Mojang, was bought by Microsoft for $2.5 billion. Most developers would have released a sequel by now, but instead the team has busied itself with console ports and updates for the “vanilla” game. Minecraft has many older fans — the average player is 29 — but in the last few years, the game has clearly benefited from an influx of younger players. They’ve helped Minecraft form a diverse gaming community spanning different ages, genders and geographies.

That expansive player base was clearly reflected at Minecon. Not just in the attendees, but also in what was offered to keep them entertained. Many of the younger Minecraft fans wanted to see famous YouTubers like Joseph Garrett, otherwise known as Stampy. Videos of his daily adventures have attracted more than 6 million subscribers and led to an online animated series called Wonder Quest. On the first day of the convention, he held an hour-long show on the main stage that featured a slew of Minecraft-themed games and activities. One, for instance, saw him teaming up with a fellow YouTuber who was trying to play the game blindfolded — a second pair picked from the crowd then raced the duo to complete challenges in the world. At the same time, the crowd was encouraged to cheer and shout out their suggestions. “Go to the meadows,” one boy screamed from the top of his lungs. “No, not there; right a bit; right a bit,” a girl farther back muttered dejectedly.

It wasn’t just Stampy whipping the crowd into a frenzy though. Some fans raced to see members of Mindcrack, a community of YouTubers and Twitch streamers that play Minecraft online. “Just meeting a couple of them was really amazing,” Nelson Jansen, a Minecraft buff who’s been playing since the very first version said. “So far, that’s easily the best thing that’s happened.” Internet personalities are an obvious draw, but for some, the event was just a once-in-a-lifetime chance to meet fellow fans.

More than 70 million copies of the game have been sold, so you would be forgiven for thinking that every schoolyard is filled with Minecraft addicts. But in reality, that’s not always the case. “At my school there’s only a few people that play it,” said Lewis Walmsley, a student from Manchester. “So it’s nice to meet other people that play — obviously they have different ideas that you can share.” Jurrien Brondijk, a fellow Minecraft player felt the same way: “It’s a big event with a lot of people that enjoy Minecraft and those sorts of things. So that’s very appealing, just to meet all those people and talk about the game.”

Internet personalities are an obvious draw, but for some, the event was a once in a lifetime chance to meet fellow fans.

Fancy dress has become a massive part of convention culture, and Minecon was no exception. At every panel, booth and queue, players would feverishly compare polystyrene pickaxes and swords covered in signatures from their favorite developers, modders and YouTubers. Some of the attendees went even further, making outfits that resemble classic monsters from the game. Unlike most video game conventions, however, the enthusiast “cosplay” scene wasn’t really apparent. Almost all of the fans in dress-up were young children and there was a rough, heartwarming feel to everything they had made. One little girl had decorated a dress to make it look like her personal Minecraft world, topped with glitter and stars for some personal flair. None of them were professional cosplayers, or hobbyists that relish the challenge of perfectly recreating their favorite character’s outfit. Instead, these were fans that just wanted to show their appreciation.

“You know you can come here and walk around with your diamond sword and no one will have a problem with it,” Sam Walker, a Minecraft player hooked on community mods, said. “While if you take it on the London Underground, you might get a few shifty looks!”

Even after hours, Minecon was an impressive sight. Huge fortresses were erected in the corners of the main convention hall, lovingly painted to look like stone, ice and sand. Statues of blocky builders guarded their entrance, while a pair of Iron Golems stood watch in the building’s central hallway. Near the back of the convention, you could wander through a series of farmyard pens filled with sheep, pigs and other Minecraft animals. During the day, there was even an opportunity to have your picture taken atop one of the horses, if you didn’t fancy leaning over the fence for a quick selfie.

“Our one and only priority is just that everyone that comes here has a good time and gets to celebrate Minecraft,” said Matt Booty.

The amazing decorations didn’t stop there. To match its London setting, Minecon offered a “Minepark,” which resembled London’s eight Royal Parks. The leafy escape had artificial grass, park benches and a bridge overlooking a river and swan. Families could gather at the tables and log stools for lunch, before wandering down the strip to take in some carnival attractions. These were, of course, all Minecraft-themed, with names such as Tic-Tack-Inventory, Creeper Catch and Mine Racer. Some were devilishly tricky, but others were simple enough so that everyone walked away with a prize.

“Our one and only priority is just that everyone that comes here has a good time and gets to celebrate Minecraft,” said Matt Booty, Microsoft’s general manager for the Minecraft team in Redmond. “I think that’s different for everybody. For some people, that means getting to meet their favorite YouTubers; for others, that’s going to be getting to meet Jens (Bergensten), the creative director from Mojang. For others, it’s going to be coming and getting to go to the panels. So I think it’s just that everybody comes away feeling that they got to somehow participate in their favorite game and got to be a part of the community.”

For Minecraft maniacs, Minecon is a special event. But the game’s popularity does beg the question: Why hold a convention at all? Minecraft is selling well and the community will grow regardless of whether Minecon is a success. Well, according to Booty, none of that really matters. Minecon is about thanking the fans and proving that Microsoft isn’t about to meddle with a winning formula. “Our approach is very much a partnership, so we’re just working together with Mojang and not looking to come in and radically change things, or try to turn them into something more Microsoft-like,” Booty said. “We mostly want to make sure that we’re a great resource and they continue to succeed.”

Microsoft and Mojang have a surplus of player feedback from social media, Reddit and the Minecraft forums. But sometimes, it’s easier to record and act upon this information by meeting people in person. Over the weekend, Microsoft hosted competitions to win one of 25 golden tickets and a rare HoloLens briefing. With this augmented reality headset, you can project and manipulate digital images in the real world, similar to Minority Report and Iron Man. Microsoft has only shown it on a few occasions and one of its most impressive demos to date incorporated Minecraft. At E3 in Los Angeles, the player was seen projecting a virtual TV screen onto a blank wall and later pulling the entire Minecraft world onto a table. In the latter mode, he could view the landscape from an aerial perspective, follow other players and interact using various voice commands. Few people outside of the press have tried it, but Minecon was the perfect place to put it in the hands of the public. “Giving players the opportunity to see something like HoloLens — I don’t know where else we could do this,” Booty said.

Minecon wasn’t just for the fans — delighting them re-energized Mojang and Microsoft employees too. The positivity inside the Excel Exhibition Centre was infectious; every panel ended with rapturous applause and during the closing ceremony, some children said they were the best days of their lives. “We all come away from this excited about working on Minecraft,” Booty said. “It’s hard to sit in the big room for the main stage or be on the show floor and see how excited everybody gets, and not come away excited yourself.”

Minecon is unusual. It’s now the largest convention dedicated to a single video game, beating events like EVE Fanfest and Summer of Sonic. But this year’s event was still small and surprisingly peaceful. Ten thousand tickets might sound like a lot, but it’s a slither of the attendees now turning up for MCM London Comic Con. Not that it really matters. Unlike most conventions, Minecon has never been about making money. It’s a celebration of Minecraft, and a way for both the fans and its creators to say thank you. A humble event for what started as a humble game.