If ever there was an event specifically designed to send the regular Sydney Opera House clientele into a near-fatal frenzy of monocle popping, it was this one: a video game festival hosted at Australia’s most famous cultural icon.

But whatever misgivings one may have about Minecraft at the Opera House, when I arrive the mood is buoyant.

Children weave in and out of bollards, cleaving the air with plastic pixilated swords, taking selfies with giant cardboard renderings of pigs, llamas and box-headed humans. More still stand in line to meet the “celebrities of Minecraft” – a concept that would be impossible to even begin to explain to someone 10 years ago. Others are marshalled into groups, waiting side stage in the concert hall to take part in Australia’s first Minecraft tournament.

The parents take in the scene with an air of contented bafflement.

Their confusion is understandable: on the surface, Minecraft as a popular game, let alone an international phenomenon, is hard to explain.

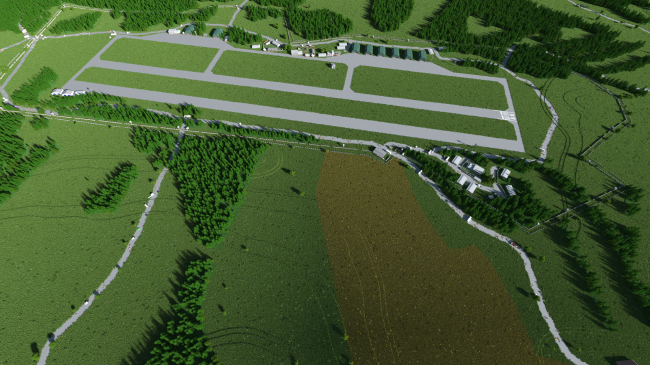

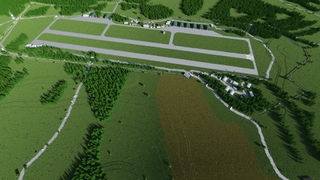

Created by Markus “Notch” Persson in 2009, Minecraft is what’s known as a “sandbox” game – a genre typically defined by an absence of clear goals or win conditions, and an emphasis on creation and free-play. In Minecraft you are born without ceremony or context into a world made up of blocks. These blocks can be mined and placed in any configuration the player desires, and for this reason the game is often described as an environment where you can build “anything you can imagine”.

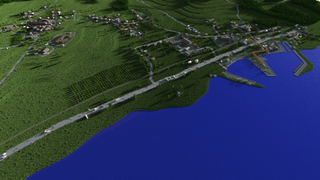

To a degree this is true, although it does suggest that the collective imagination of the hive mind is overwhelmingly preoccupied with creating enormous effigies of Super Mario. In the past, players have used the game’s universe to build painstaking reconstructions of Taj Mahal, the International Space Station and – of course – the Sydney Opera House.

Australia’s first Minecraft tournament is playing out in the main concert hall. With three sessions over the course of the festival, and each session comprising seven rounds with 48 children per round, over a thousand kids will compete over the two days. At the start of each round, four dozen children are marshalled on to stage, organised through a system of coloured wristbands that, throughout the hours I am at the event, I will never understand.

The version of the game used for competition is rapid and combat-based and so this experience is less about the unchained power of the imagination and more about shoving one another into big pools of lava. There is little to no mining or crafting in this iteration of the game, and at the end of each round, the winning children are interviewed by the host, who quizzes them on their strategies, their faces projected on to a gigantic screen at the back of the stage.

According to an astonishingly fashionable kid in a leather jacket and asymmetrical haircut, the trick is to “get a weapon and run”. The host can’t fault this and asks for a high five. Leather jacket kid opts for a fist bump.

Outside the concert hall, the back foyer bar hosts banks of PCs manned (child-ed?) by dozens of kids working on a more recognisable form of the game. Block by block, like the medieval lords of yore, they build enormous garrisons, undertake large-scale agricultural projects and – possibly less like the medieval lords of yore – ward off demented skeletons with swords forged from pure diamonds. This space in the Opera House typically given over to baby boomers quaffing $14 riesling is now full of kids waiting in line (it must be said, far more patiently than I’ve seen boomers queue for riesling) for the chance to make something unique from scratch.

The popularity of Minecraft content on YouTube and Twitch is staggering: in fact, “Minecraft” is the second-most searched term on YouTube, just behind “music”. Perpendicular to the free-play area there’s another line, this one maybe 50 deep, to talk to Wyld and MrCrayfish: two celebrity Minecrafters with massive profiles on both YouTube and Twitch.

These two affable men sit behind a small table and receive their visitors one at a time, leaning in close to hear deeply technical questions from the kids. The overwhelming majority of these questions are impenetrable to the layman, and watching each and every parent nod along with their kid while one of the experts explains an insanely specialised aspect of, say, complex redstone systems, is genuinely heartwarming.

Like the game itself, the sheer scale of Minecraft’s success can be difficult to comprehend. Statistics can tell part of the story. At the time of writing, around 55 million players log into the game each month; in 2016 the game sold around 55,000 copies per day; and in 2014 it was sold to Microsoft for $1.5b, allowing Persson to retire and pursue another of his passions full-time: being insanely cross on the internet.

The lead developer and designer is now Jens Bergensten, a tall, rake-thin and bearded Swede who, throughout the day at the Opera House, will wander into the foyer to greet fans. The first time I see him he’s at the business end of a massive line of devotees, dutifully signing posters, posing for photos and answering questions.

There’s a calm awkwardness about Bergensten. It gives him an air that’s less “mogul at the helm of a multi-billion dollar empire” and more “viking who has become lost at the shops”.

The live event is meant to reflect the ethos of the game, I’m told by the COO of Mojang, Vu Boi, who has travelled with Bergensten to the event. Just as there’s no one way of playing Minecraft, there’s no one way to experience the day.

He’s not wrong about this, but there’s something else too: the game itself is the second-most perfect encapsulation of the seamless meeting of “high” and “low” art that I can think of (the most perfect being the time that Salman Rushdie became addicted to Super Nintendo). Bringing a video game to the hallowed sails of the Opera House is a neat expression of that philosophy.