Free book for boys and reluctant readers

Flynn’s Log is free on the following devices

Choose your device

KindleiPad/iPod/iPhoneGoogle Play (Android Tablets)nookkoboRead Online

US$8.99 Paperback

Get Reluctant Reader Book News from Stone Marshall

Reading is important

Any book that helps a child to form a habit of reading, to make reading one of his deep and continuing needs, is good for him. –Maya Angelou

Most adults would agree that reading is important, but many kids detest reading. Video games, devices, and TV are preferred entertainment and escape. They provide instant gratification. Reading takes time. For some kids, reading isn’t engaging.

I had this same problem with my son, so I solved the problem.

The classic stories I remember enjoying as a kid don’t interest my son and his immediate attention span. If he doesn’t enjoy the story from page one, he will not read further.

So how did I get my son to read?

I showed him how much fun it is to get sucked into a story.

Your book is amazing I can’t stop reading it – Joseph Young via twitter

Contemporary and Classic titles alike don’t interest many kids. Don’t worry, the love of reading is learned. We need a starting point. We need that one book that is just as engaging on the first read as the fifth, just like a really great movie that kids want to see again and again. A positive association with reading will make kids want to read more.

A love of reading is cited as the number one indicator of future success. My son didn’t have the desire to read. He didn’t care about the books I chose to read to him, and was overwhelmed with the selection at the library. I want my son to succeed, so I had to do something. Since we struggled to find books he cared to read, I wrote one. An epic saga about the things he loves. I put it in a world he loves and addressed the issues he faces in his life.

I just love your books I’ve been reading them over and over again. -Carson via twitter

But it’s a video game book

Don’t worry; it’s not a book about video games, nor is it a game strategy book. Flynn’s Log is a hero’s journey that takes place inside the Minecraft world that today’s kids know and love. The protagonist, Flynn, naturally flows through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (builds shelter and tools, learns what to eat and discovers a digital friend) and faces questions about his destiny. He learns important life lessons about friendship, integrity, and trust. Flynn’s Log is good for kids without being boring.

Thank you so so much for the free ebook. My son loves Minecraft now with this book I can get him to read to me. – Jennifer Wilkins

Start your son or daughter on journey today, reading Flynn’s Log 1: Rescue Island. Free on available these devices and apps.

Flynn’s Log is free on the following devices

Choose your device

KindleiPad/iPod/iPhoneGoogle Play (Android Tablets)nookkoboRead Online

US$8.99 Paperback

Why is Flynn’s Log 1 Free?

My son loves reading — finally. If you have experience with a reluctant reader then I know your pain and I want to help. I’ve seen thousands of kids transform with this book. My readers, who don’t usually read books during the summer, couldn’t put Flynn’s Log 1 down.

Good book I thought I would never read a book on my summer but I feel I’m gonna finish it soon – Multigamer 47 via twitter

Let this book change your kid’s life too. You have nothing to lose and an avid reader to gain.

Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.

–Frederick Douglas

I am giving away Flynn’s Log 1 free because I want to give you a risk-free way to hook your reluctant reader.

Please and I mean PLEASE, WRITE MORE! I absolutely love it! They’re outstanding books.

-Devon123321 via twitter

What are Books for Boys?

I spend lots of time with teachers and parents. I hear parents ask, “How do I get my son to read? Do you have books for boys?”

I wrote the Flynn’s Log series for my son, and this book is interesting for boys. However, the series is a non-stop read for both boys and girls, especially those who are interested in Minecraft.

The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.

—Dr. Seuss

What are you waiting for?

You have nothing to lose!

Flynn’s Log is free on the following devices

Choose your device

KindleiPad/iPod/iPhoneGoogle Play (Android Tablets)nookkoboRead Online

US$8.99 Paperback

News for Parents of Reluctant Readers

Get Reluctant Reader Book News from Stone Marshall

Fortnite passes Minecraft as the world’s favourite video game

As the mobile version goes live for selected players, other publishers are worrying the success of Fortnite could cut into their profits.

It didn’t seem as if Fortnite had any more records to break, after overtaking PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds and becoming the most watched game on Twitch, but now it’s also the most searched for video game on Google – surpassing even Minecraft.

Fortnite also got more searches than the term ‘bitcoin’ and is now estimated to have been played by 45 million people worldwide.

This is of course great news for Epic Games, who confirmed today that invites to play the iOS version of Fortnite Battle Royale, have gone out to certain fans.

But analysts are worrying that the success of Fortnite means problems for other video game companies.

‘We believe the strong growth of Fortnite creates tactical risk to the video game publishers’, said analyst Evan Wingren, as reported by CNBC.

‘The game is gaining momentum in Western markets, which is likely to impact engagement for all AAA games to some degree. We believe Fortnite is growing the overall gaming TAM [total addressable market], but some cannibalisation is likely.’

Rather than forcing EA and Activision execs to eat their rivals, what this means is that other publishers are likely to make about 10% less revenue from their own multiplayer games – because everyone’s spending their time and money on Fortnite.

Fortnite only seems destined to get more popular though, especially considering the mobile versions haven’t even launched properly yet.

Footage of the game on iPhone and iPad is starting to appear around the Web though, and if you want to try and sign-up yourself the link is here.

Email gamecentral@ukmetro.co.uk, leave a comment below, and follow us on Twitter

Fortnite passes Minecraft as the world’s favourite video game

Nintendo Switch isn’t just a console, it’s a 127-year saga that began with a deck of cards

To explain where the idea for the Nintendo Switch came from, Yoshiaki Koizumi puts his hand into his jacket pocket and pulls out a Nintendo-themed playing card, placing it on the coffee table in front of him. Look back 127 years, he continues, to Nintendo’s founding in September 1889. “Nintendo made playing cards,” says Koizumi, 48. As deputy general manager of the company’s entertainment planning and development division, he’s been one of the leading creative influences behind the Switch. “Playing cards are something that you enjoy eye-to-eye with another person,” he says. “Think about a deck of cards. It’s something that is small, many of the games have rules that are easy to learn and people of all ages can enjoy playing them together.” For a deck of playing cards, his thought experiment goes, substitute a games console. The secret to Nintendo’s innovation, he concludes, is simple: “It’s not necessarily about technology.”

Nintendo’s philosophy for making games has often been counterintuitively low-tech. “A lot of the history of gameplay, up until this point, has been people looking at a screen, not necessarily seeing the facial expression and the body language of the person next to them,” says Koizumi. “So that became a very important, fundamental concept for us moving forwards on Switch: how to preserve that, how to bring people back to that kind of experience.” Whenever he attempts to explain Nintendo’s thinking with Switch, and its approach to game development in general, Koizumi comes back to playing cards: play anytime, anywhere, with anyone and always see how they react. “If I were to put it into incredibly simplified terms, we don’t necessarily view this as a gaming machine, we view this as a tool for play,” adds Shinya Takahashi, 53, director and general manager on the same team as Koizumi. The word “play” – and its distance from the word technology – crops up a lot at Nintendo. In an interview with Edge magazine for the GameCube’s launch in 2001, Nintendo’s late president Satoru Iwata said the company’s ambition with its software was to “satisfy people’s need to be happy.” The GameCube sold 21.74 million units to the PlayStation 2’s 155 million. The Wii, Nintendo’s next console, sold 101 million units to the PlayStation 3’s eighty-five million.

I meet Koizumi and Takahashi in a hotel room in South Kensington, London. Both sit on a sofa flanked by oversized, floral cushions, attentively listening to my questions in English before turning to an interpreter. Koizumi is the more smartly dressed of the two, the fringe of his hair swept carefully to one side, a Nintendo Switch lapel badge pinned proudly on his grey jacket. Takahashi, livelier and more excitable, fixes me with his gaze whenever I speak. “You’ve both worked for Nintendo for a couple of decades, is that right?” I ask. “Twenty-eight years,” says Takahashi, pausing to do some mental arithmetic. “Nineteen-eighty-nine!” he adds. “Nineteen-ninety-one,” chirps the ordinarily straight-faced Koizumi.

Takahashi and Koizumi’s curriculum vitaes read like a birthday wish list from my childhood. One of Takahashi’s first jobs was as a designer on Wave Race 64, he was also producer on Mario Kart: Double Dash!! and general producer on Dr. Kawashima’s Brain Training. Koizumi was assistant director of Super Mario 64; director of Zelda: Ocarina of Time; Majora’s Mask; Super Mario Sunshine; Donkey Kong Jungle Beat; Super Mario Galaxy; Super Mario Galaxy 2; Super Mario 3D Land and Super Mario 3D World. The pair, with their combined half-century of service, have played a key role in shaping the company’s next big hope.

The joyous idiosyncrasies in the Nintendo games I played, and still play, are what make them stand out. Accompanied by countless others, I am the intrepid explorer in the worlds it creates. In 1997 I glided through the serene landscapes of Pilotwings 64, watching the Space Shuttle take off from a virtual Cape Canaveral on Little States Island. My childhood friends and I raced around the upper deck of Block Fort in Mario Kart 64’s Battle Mode. Galloping across the fields of Hyrule in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, it felt like I was venturing out alone against an insurmountable enemy. At their best, Nintendo’s games have always had an intangible, brilliant weirdness. That happy knack has a lot to do with heritage, which is more keenly felt at Nintendo than other games companies. For Takahashi, who has spent his entire adult life building on that heritage, the feeling of pride is clear. His favourite moment as a developer remains the time he saw someone playing a demo of the first game he had worked on, a little-known SNES title released only in Japan. “To see their reaction, to see the joy on their face,” he says. “That’s a memory that I’ll always keep.”

Shinya Takahashi, one of the leading creative minds behind the Switch, has worked at Nintendo for twenty-eight years

The launch of Switch comes at a tumultuous time for Nintendo. Its debut smartphone game, Super Mario Run, was released in December 2016, five years after Iwata warned that doing so would cause Nintendo to “cease to be Nintendo”. In March 2015, as the company announced plans to develop games for smartphones, Iwata admitted it would be “a waste” not to. “It is structurally the same as when Nintendo, which was founded 125 years ago when there were no TVs, started to aggressively take advantage of TV as a communication channel.”

In 2014, it was Iwata, in collaboration with The Pokémon Company’s Tsunekazu Ishihara, who conceived of the idea of Pokémon Go, inspired by a Pokémon-themed April Fools’ Day gag on Google Maps. Launched on July 6, 2016, the game now holds the record for most revenue grossed by a mobile game in its first month ($206.5 million), most downloaded mobile game in its first month (130 million), most mobile app store charts topped simultaneously (70) and the fastest mobile game to gross $100 million (20 days). Nintendo owns a thirty-two per cent stake in the Pokémon franchise and an undisclosed stake in developer Niantic. Something, somewhere, had changed Iwata’s mind.

Iwata passed away in July 2015 at the age of 55. He wasn’t around to admire the record-breaking success of his collaboration, but his way of thinking still dominates Nintendo. “On my business card,” he said during a speech at the Game Developers Conference in 2005, “I am a corporate president. In my mind, I am a game developer. But, in my heart, I am a gamer.” Iwata, like Mario-creator Shigeru Miyamoto, composer Koji Kondo, GameBoy-inventor Gunpei Yokoi, Takahashi, Koizumi and many others, all got what it meant, and still means, to work for Nintendo. “Typically, you go to a programmer and tell them what you, as a designer, want to do. They then tell you all the reasons why you can’t do that,” Shigeru Miyamoto told The New Yorker in December 2016. “Mr. Iwata was different. He felt it would be shameful for him to say something was impossible.” It’s a cliché that listlessly flops out the mouths of many company executives, but Iwata’s sentiment feels different – and it all rests on the word “shameful”.

For Nintendo’s rivals, achieving the impossible is oft-linked to rapid growth and big profits. Nintendo is, at times, confusingly different. In a speech delivered in 2011, Iwata drew a clear line between his company and its smartphone competitors. “Their goal is just to gather as much software as possible, because quantity is what makes the money flow.” Nintendo, he implied, was different. That same year, Iwata finished the point he had started: “I believe my responsibility is not to short-term profits, but to Nintendo’s mid-and-long-term competitive strength.” It’s an attitude that helps explain the company’s stoic response to its failures: Nintendo had expected to sell 100 million units of its Wii U console, in the end it shifted closer to thirteen million. The Switch must do better.

Nintendo’s Yoshiaki Koizumi demos the Switch during its unveiling at an event in Tokyo in January 2017

When it launches on March 3, the Switch will cost £280. Nintendo is releasing the two major day-one titles – 1-2-Switch and The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild – with Konami’s Super Bomberman R, Activision’s Skylanders: Imaginators and Ubisoft’s Just Dance 2017 completing the line-up. Before the end of 2017, Nintendo will add Mario Kart 8 Deluxe, Splatoon 2, Super Mario Odyssey and ARMS, a new, fast-paced fighting game that makes full-use of the innovative Joy-Con. Fire Emblem Warriors, Xenoblade Chronicles 2, Sonic Mania and a clutch of other high-profile titles from third-parties will also be available before the year is out. As ever, Nintendo will be hoping a small selection of big names can help lift an otherwise lacklustre line-up.

In recent generations, Nintendo’s home console successes have tended to come in fits and starts: the Nintendo 64 sold relatively well, the GameCube poorly, the Wii was a runaway success, the Wii U a runaway failure. But, from Wii to Wii U to Switch, Nintendo’s thinking has become clearer. The Wii, with its intuitive motion controls, opened up play to everyone, while the Wii U’s tablet-like controller laid the groundwork for the Switch’s far more polished, portable design. Takahashi describes it as a “unified system”, a blend of handheld and home console, finally made possible by the technology available to Nintendo. “It just so happened that various technologies were coming together,” adds Koizumi “And we saw that we could combine them together to solve exactly that problem. And that, I think, was the real inception of the Switch.”

The careers of Koizumi and Takahashi, both arts graduates who have worked for Nintendo their entire adult lives, are typical for a company whose employees pride themselves on lifelong devotion. “We started just a few years before the N64 era,” says Takahashi. “When we were making that shift from 2D to 3D gaming with the N64, we were two of the main individuals within Nintendo who were really leading the designers and helping to draw them out of that 2D world and into 3D game design,” he adds, pausing thoughtfully. “To put it more simply, the two of us like doing new things.”

While much of the press attention, and Nintendo’s own marketing, has focussed on how the Switch is both a handheld and home console, Takahashi seems more enthused about the new Joy-Con controllers. The palm-sized red and blue batons, packed with accelerometers, gyro sensors, infrared cameras and no fewer than 22 buttons, promise both confusion and potential. Takahashi asks if I’ve played a 1-2-Switch minigame where you have to guess the number of balls inside the controller, an impressively realistic sensation created using HD rumble, another feature squeezed into the palm-sized Joy-Cons. It’s a seemingly inconsequential feature that, for Takahashi, could change the way people play games. For the first time, players are asked to play a game where they’re not meant to look at the screen. It’s a very ‘Nintendo’ idea.

Takahashi asks what other 1-2-Switch minigames I’ve played. I reply while miming milking a cow. He laughs enthusiastically. “You seem like you liked that,” he says, laughing again. Whether guessing the number of balls, milking a cow, having a Wild West shootout or unlocking a safe, all the minigames in 1-2-Switch have one thing in common: you look at the person you’re playing against, not the screen. “If you play 1-2-Switch you get a sense for what we were trying to achieve with the hardware,” Takahashi continues. “We didn’t start with the idea of trying to create an integrated device that combined a home console with a handheld. Instead, we started with the idea of wanting to create a device that had a versatility of play that could appeal to as broad of an audience as possible.”

Nintendo’s games have always had the ability to turn us all into children again. When someone gets nostalgic about their childhood, I tend to warp-pipe back to a time of leaping plumbers, drifting go-karts and Pikachu electrocuting Captain Falcon. And as with any great creative work, a great game needs a soul. “Those of us who are working on the software side are always worried about one thing: how to get players to empathise with what they’re seeing in the game,” says Koizumi when I ask about the role of emotion in Nintendo’s games. “We’re always looking for ways to make different elements of the game the exact balance of surprise and empathy, which kind of play opposite one another to create that experience.”

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the Switch’s most high-profile launch game, is also being released for the Wii U

For Nintendo, nowhere does that balance play out more than in Zelda, a franchise Koizumi has worked on for nearly two decades. So what can people expect from the latest instalment? “I think you’re going to find a lot of elements that really bring it back to the very first Zelda game, in the sense that people will find puzzles as they explore and get to solve them,” he says, referring to Breath of the Wild. Previously, Link’s world was alive to a point, now it teems with weapons, secrets and foes. “It also brings in some new elements like this idea of a wild, natural world surrounding you and challenging you to survive,” explains Koizumi. That battle to survive is not just at the core of Zelda, but also a challenge Nintendo must face as it approaches the launch of its latest console. “In that sense this Zelda has a story to it, of course,” says Koizumi. “But the adventure is bigger than that, it’s about the entire world as well. And that world is very wild.”

Despite the commercial ups and downs, Nintendo continues to innovate and surprise. “The source of our creativity, really, for the past thirty-to-forty years has come from the fact that we don’t look at what other companies are doing and try to replicate their success,” says Takahashi. “The core of Nintendo culture is this feeling that if all we do is replicate somebody else’s success, we’ll never actually achieve the same level of success that they had.” That, continues Takahashi, is the reason for Nintendo’s reputation as a highly-secretive company. “We’re so busy thinking about things that other people aren’t doing,” he says, half-smiling. “We don’t want to tell people what we’re thinking about because then other people might do it.”

Nintendo Switch isn’t just a console, it’s a 127-year saga that began with a deck of cards

Playing online games can make children smarter (just don’t let them use social media)

Parents – don’t worry about your children spending all their time online playing games. It may actually be improving their performance at school.

That’s according to new research from RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. The institution found that playing games could help students in sharpening skills learned at school, and then applying them elsewhere.

Research was conducted by Alberto Posso, associate professor at RMIT’s School of Economics, Finance and Marketing. Posso investigated data from the globally recognised Program for International Student Assessment, scraping the test results from more than 12,000 Australian 15-year olds.

Posso looked at tests covering maths, reading, and science, while also collecting data on students’ online activities. Those who played online regularly saw sharp improvements in academic performance over those who did not.

“Students who play online games almost every day score 15 points above the average in maths and 17 points above the average in science,” said Posso.

“When you play online games you’re solving puzzles to move to the next level and that involves using some of the general knowledge and skills in maths, reading, and science that you’ve been taught during the day,” Posso added. “Teachers should consider incorporating popular video games into teaching – so long as they’re not violent ones.”

The integration of gaming and education is nothing new – educational games have existed almost as long as personal computers. However, recent years have seen the growth of collaborative, online learning experiences using the medium, with the likes of Minecraft having its own Education Edition.

However, while gaming can have beneficial results, social media may have the opposite effect. Posso’s research found that students who visit Facebook or other similar sites daily are actually more likely to fall behind in subjects such as maths, reading, and science – some as low as 20 points worse than those who never use social platforms.

“Students who are regularly on social media are, of course, losing time that could be spent on study – but it may also indicate they are struggling with maths, reading and science and are going online to socialise instead,” suggested Posso.

“Teachers might want to look at blending the use of Facebook into their classes as a way of helping those students engage.”

Posso does highlight that other factors could have major impacts on teenagers’ academic progress though, suggesting that repeating a school year or skipping classes has a far greater negative impact than a Facebook addiction.

Real-world community divisions could also influence development to a worse extent than social media. The study found that “indigenous students or those from minority ethnic or linguistic groups” were at “greater risk” of falling behind than teens that engaged in high use of social media.

Posso’s full research, Internet usage and educational outcomes among 15-year-old Australian students, has been published in the International Journal of Communication.

Playing online games can make children smarter (just don’t let them use social media)

Wrightcraft: Minecraft Meets Frank Lloyd Wright

The following is a republished account written by Kate Hedin, who recreated some of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous projects on the popular video game platform, Minecraft. Her work is known as Wrightcraft. This was first published on the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

I started with one of my favorite Wright buildings: the Robie House, in Chicago. I had visited the house in person several times, and even took one of the multi-hour in-depth tours, leaving me with a whole album of photos from my trip and a memory of being in the space. Next, I did a bit of research online. I found blueprints and floorplans of the house, as well as additional photos from angles and locations I didn’t have access to on my trip.

Now came the task of recreating this structure in Minecraft.

One of the biggest challenges of building in Minecraft exists in the very premise of the game: every item occupies a one cube unit of space — there are no curves, no diagonals and no angles other than right ones. Furthermore, there is also a rather limited color/texture palette to work with. Though initially this set of fixed variables might seem restrictive, I found this type of problem-solving puzzle quite exciting.

I knew I wanted the build to be as close to scale as possible (rather than up-scaling it to gain a finer granularity of detail) — I wanted to actually be able to walk around inside the house. Reviewing the blueprints of the house and Minecraft’s set of fixed variables, I decided on two elements to help set my starting reference point: Minecraft’s “door” block and the height of your character in-game. From there, I was able to lay out an outline and get a sense of scale, and then I built up from there. The Prairie Style of the Robie House lent itself quite well to the block-palette of Minecraft, and I was quite pleased with how my first build turned out.

I enjoyed the process and the outcome so much that it sent me down the rabbit hole of wanting to recreate more and more Wright buildings. So, just as I’ve added Wright buildings to my collection by visiting them over the years, I’ve now begun literally adding Wright buildings to my collection — all inside this virtual space.

The 2018 beginner’s guide to Minecraft

Minecraft is fast approaching ten years of being one of the world’s most popular games, with hundreds of millions of active players across all platforms. It has revolutionized the industry and has turned some of its most talented players into multi-millionaires. It dominates YouTube, is on the shelves of every toy store, and it even has its own Lego range.

Some people play Minecraft because it offers a lot of creative freedom; Minecraft has been used by architects and in schools as an educational tool. For others, it’s the adventure; such a vast world can be explored endlessly and provides hours of entertainment.

If you’re late to the party and have only just bought the game, you might not know where to start. The game drops you into a very vast world, and it can be a very confusing game to get started with. Each world is randomly generated from a string of numbers (known as a seed), so no two worlds are the same. Fortunately, once you’re armed with a few basics and a pickaxe, you’ll learn the ropes in now time. So let’s dive into the basics.

The 2018 beginner’s guide to Minecraft

Crafting

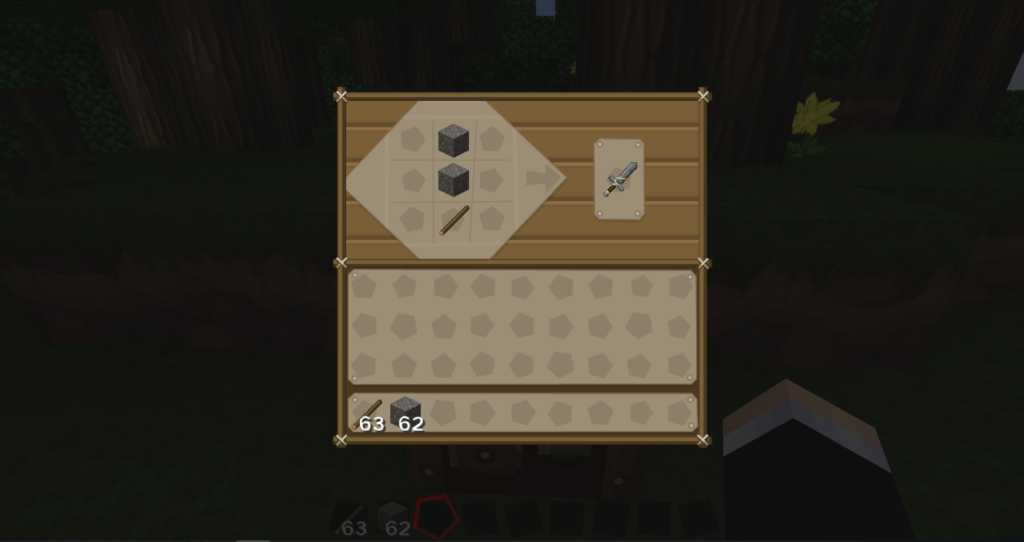

Crafting is central to the game, and is used to make all kinds of different objects from the materials you have. Each item in the game – such as a sword – has its own individual crafting recipe. For example, to make a stone sword, you would craft it like this:

Placing a stick below two pieces of cobblestone would make a stone sword. Swap out the cobblestone for wood, iron, gold or diamond to create different variations, diamond being the strongest and most durable.

Before you start crafting anything, however, you will need to build a crafting table, which is made from four pieces of wood. This is a very simple process and can be done as soon as you step foot into your first world.

How to build a crafting table

- Locate a tree and then punch out some wood by holding down left-click.

- Press the e key to open your inventory and select the wood, placing it into the four boxes next to your avatar. Four oak wood planks will appear.

- Click the oak wood planks and drag them to your inventory. The original piece of wood will disappear because you have turned it into planks.

- Then, fill the four boxes where you placed your original piece of wood with the four wood planks. A crafting table will appear.

- Drag the crafting table to your hotbar (the single line of boxes) and then exit your inventory. The crafting table will appear in your hotbar and you can select it by scrolling. When it’s selected (i.e. it is in your hand), place it on the floor by right-clicking.

You now have a crafting table, which is a 9×9 area that allows you to craft anything in the game; just right-click the crafting table to use it.

It is important to know how to utilize the crafting feature so you’re ahead of the game when it comes to surviving your first night in Minecraft, because you won’t have long until it’s dark and monsters spawn. Speaking of which…

The first night

Your first night in the game is the hardest because you start with nothing. When you spawn for the first time, the in-game time is noon. You only have a short amount of time (ten minutes) to get a basic shelter together in order to survive. If you don’t build a basic shelter, you’ll spend your first night repeatedly getting mauled by mobs – not fun!

To survive your first night, you’ll need to grab yourself some wood to build a basic shelter and create some wooden tools, then hunt down some coal to make a couple of torches. Mobs (monsters) spawn in the dark; you really don’t want to create a shelter and then have a monster spawn inside it!

What exactly are “mobs”?

“Mobs” is the term used to describe Minecraft’s animals and monsters. Mobs can either be passive (such as sheep or pigs) or aggressive, and there are many different adversaries in the game that have the potential to harm you or destroy your creations.

Over the years, mobs have been a huge focal point for the Minecraft development team, and the number of mobs has virtually doubled. However, the mobs you should pay special attention to while you’re still finding your feet are the aggressive ones that can spawn in the Overworld.

Zombies are quite easy to fight; you just need to keep hitting them. Zombies will come after you if you get within a certain radius of them, and they can beat down doors. They are very slow and aren’t a huge threat, but a group of them can be deadly.

Spiders only attack you at night. These pesky monsters have the ability to climb walls, jump and move fairly quickly, though, like Zombies, they are quite easy to kill… most of the time.

Skeleton Archers are a serious threat even for experienced players. This very irritating monster carries a bow and arrow and has the ability to shoot you with it. As a result, these monsters can do damage to you from a considerable distance, and they are very accurate.

Creepers are perhaps the most widely known and most destructive of mobs in the game, especially when you are just starting out. Creepers explode when you get within a certain radius of them and can decimate small bases. It takes them a couple of seconds to explode, but they will chase after you, so just stay well away!

Endermen are the final mobs you need to worry about in the early stages of your Minecraft life. These tall, dark, and slender mobs may look pretty scary… because they are. Endermen are passive… until you look at them… and then you’re going to die, probably, because they have the ability to teleport away from and then back to you, attacking from a different angle. Just keep as far away from them as possible; you don’t stand a chance as a new player!

Mining

As you have probably guessed by the name “Minecraft,” mining is pretty much the most important aspect of the game. When you’ve survived your first night, have a basic set of tools, and know which nasty monsters to look out for, you’re set to begin delving underground and exploring the world beneath you.

The world extends down below the grass by around 100-130 blocks; it is here where you will find all the best resources, treasures, and loot. You’ll find iron, diamonds, and gold, with which you can create more durable tools; and redstone, which is Minecraft’s answer to electricity and can be used to make circuits.

It is best to start mining below your shelter, because then you are safe from monsters and you don’t need to run through the wilderness to get home and risk being attacked by a monster. Don’t dig straight down, though, or you may fall into lava or a chasm.

The best way to mine is to dig in a stairway pattern; that way you avoid falling into deadly pits and have a clear pathway to get back home. No matter what method you use to mine, though, always make sure you have a plentiful supply of torches and food; it is dark underground, which makes it hard to see and is the perfect environment in which monsters can spawn and ruin your day!

It is easy to get lost in mining, and people often spend many hours doing it… it is quite therapeutic, and Minecraft’s ambient music only adds to this. Remain vigilant at all times, because monsters do spawn underground in pre-existing caves and dungeons… in fact, it can be just as dangerous below ground as it is above ground.

Now that you have the basics of Minecraft down, take your gaming to the next level with our guides to how to install Minecraft mods and how to change skins in Minecraft.

Gaming more than a Space Oddity

A ruthless online space game is stretching the boundaries of fun, telling us about ourselves and the wider potential of gaming

How does this sound for some gaming fun … or not?

You spend hours of computer gaming time building spaceships and learning a complicated combat system that requires working a spreadsheet. Then you fly into space where there are no rules, where you can’t trust anyone, and where you are likely to get blown up and stolen from by online gangs of bullies, potentially losing all you had invested hours in building.

No thanks, just pass me the remote.

But for over half a million people the massive multiplayer online space game EVE Online is right up there with their idea of fun. It is a gaming phenomenon that is now attracting serious academic study as it pushes the boundaries of what constitutes ‘fun’ for people. Its longevity and success is posing deep questions about what we want from games, what they can tell us about ourselves, as well as suggesting new avenues for applying gaming concepts to the real world.

It is the real sense of meaning that can be generated in otherwise frivolous virtual worlds that is key to EVE’s success and perhaps the wider applicability of gaming, says University of Melbourne human computer interaction researcher Dr Marcus Carter.

Unlike most online games, EVE, launched in 2003, imposes serious consequences for failure, and creates a harsh and cold environment where there is no reset. Once a player takes an action it can’t be taken back or replayed, and the impact can affect every other player in the game.

“EVE can generate an enormous amount of meaning because as in the real world every decision can only ever be made once,” says Dr Carter, who has edited the first book to examine the EVE world, Internet Spaceships Are Serious Business, published earlier this year.

“It shows the enormous breadth of ways in which games can be attractive to people. The appeal of EVE Online is completely alien to most people, but that is why I’m interested in it. It is a contrasting case that challenges how we think about virtual worlds and online communities,” he says.

In EVE, when players fight their space wars they risk permanently losing hundreds and even thousands of hours of game time that some will even have spent real money to acquire. For the players it is more than enough to focus the mind.

It encourages wholesale deceit and espionage that extends well beyond the game, including infiltrating off-game forums to sabotage competing alliances. Once there was even a plot by some players to cut the power to an enemy’s house in London to take them out of an upcoming battle. Sometimes players are forced to set their alarms for the middle of the night so they can get up in time to defend themselves against co-ordinated attacks launched from different time zones.

To protect themselves players band into alliances, some of which boast tens of thousands of players. The largest has 40,000 members, is led by one player named The Mittani, and is known appropriately as The Imperium. The hundreds of thousands of players have in effect evolved their own Star Wars and made their own stories, some of which have been compiled into a book.

real world conflict

And just as the game intrudes on the real world, the real world intrudes on the game. When Russia invaded the Ukraine in 2014 a group of Ukrainians players who were allied with some Russian players suddenly betrayed their partners and defected.

“EVE Online shows that negative things can be part of the attraction of playing games – that ‘play’ can involve struggling to survive in a hard, ruthless and high stakes world. People will question how it can be fun to be stolen from, to be lied to, and to be victimised. But for EVE players it is fun, and that is really interesting,” says Dr Carter.

“By playing a game we are pursuing an emotional experience such as fun or excitement. But people don’t realise how often the experience we seek in games can be something other than frivolous, but something serious,” he says. “It suggests that gaming and virtual worlds can be highly effective in motivating people toward achieving goals whether they are personal or professional.”

The key to EVE Online is that the game takes place on a single computer server, distinguishing it from other massive multiplayer online games such as World of Warcraft that take place on multiple servers, putting the virtual world into compartments. But in EVE there is only one world with all 500,000 players in it. And the game designers have taken a back seat, leaving it to the players to create their own play and providing little protection for players from each other.

In such a world it is no surprise that players band together and that alliances are perhaps dispiritingly based on real world ethnicities and cultures. EVE players are overwhelmingly male, white and work in IT. But Russians band with Russians and Reddit users band with Reddit users.

It shows that social prejudice transcends the real world.

“In a game that forces you to trust people when you can’t actually trust anyone, it is no coincidence that players band together with people that seem to be like you,” Dr Carter says.

“It is depressing, but it is also comforting that perhaps this is simply what people are like and that the more we realise that the more we can think about what we can do to stop that affecting our societies in negative ways.”

The game also puts a premium on building social skills, says Dr Carter. He describes EVE Online as a form of “social combat” in which players learn to deceive and spot deception. Some players even report becoming more socially confident through playing the game.

At the same time, the absolute dependence of EVE Online players on each other in a bleakly unforgiving environment means learning to trust someone is crucial to survival.

“It raises the stakes of in-game friendships because people have to be better friends in order to trust one another,” Dr Carter says.

How EVE Online encourages players to interact could have important implications for how we use virtual worlds and gaming ideas for other purposes such as teaching, learning and promoting social interaction for isolated people such as the elderly, Dr Carter says.

“By studying games like EVE that are on the boundary of what games can be, we can appreciate that the space for games is wider than what we may initially have anticipated.”

The tagline for the 1979 movie Alien was “in space no one can hear you scream.” But when it comes to EVE Online the screaming is audible … and worth listening to.

Banner image: Wake Up Freeman/Flickr

The best Nintendo Switch games

The Nintendo Switch has finally been revealed, and Nintendo looks set to come out swinging when the new console is launched on March 3. As well as splitting the difference between home and handheld gaming, the Switch is bucking recent Nintendo tradition by having a stellar line-up of Nintendo Switch games announced already. Here are all the highlights revealed, to date.

Super Mario Odyssey

In Mario series lore Mario and Luigi are from Brooklyn, New York (well, sometimes) but it’s never been a world the colourful, mushroom-gobbling plumber has adventured in – until now. Super Mario Odyssey sees the cartoonish hero running around both the familiar Mushroom Kingdom and new, realistic city environments, interacting with full-size humans and wall-jumping up skyscrapers. Throw in new abilities thanks to his now-sentient hat – which can be thrown like Wonder Woman’s tiara to attack enemies or create a temporary platform to jump across – and this is easily the Nintendo Switch‘s first ‘killer app’.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

The title of ‘killer app’ might go to the latest Zelda, and the only reason it doesn’t is that it’s a split release, also coming to Wii U. The prospect of console quality Zelda on the go is tantalising though, and with more than 100 dungeons, a vast open world, and deep crafting mechanics to mix up the usual gameplay formula, this coule redefine ‘epic’.

1-2-Switch

The Nintendo Switch’s answer to Wii Sports, 1-2-Switch is a mini-game collection designed to showcase the hardware’s features. In total, there are 28 of these mini-games to get to grips with, nearly all of which are played by looking at your opponent, not the screen.

This may sound odd but it takes gaming into real space, with players psyching each other out face to face before quick-draw shoot-outs, or waving the Joy-Con controllers around like swords. A contender for best party game.

– Read WIRED’s 1-2-Switch review

Super Bomberman R

Possibly the biggest surprise of the Nintendo Switch’s reveal – Bomberman is back! Konami, having been almost dormant on console games since Metal Gear Solid V, seems to have realised the wealth of its gaming IP, and is bringing one of its most beloved franchises to potentially the best platform for it. The social and portable aspects of the Nintendo Switch combined with Bomberman’s simple but addictive mechanics could be the perfect pairing.

Lego City Undercover

History repeating itself? Lego City Undercover was originally released on the Wii U, where it became the best Lego game that barely anyone played. Loosely inspired by Grand Theft Auto, with cop Chase McCain returning to Lego City to track down his criminal arch-nemesis, it remains one of the best Lego games ever made. This remastered version – which is also coming to PS4 and Xbox One – makes its bow on Nintendo Switch though, now with extra features. Hopefully, it’ll finally reach the audience it deserves.

Xenoblade Chronicles 2

The original Xenoblade Chronicles never got a fair turn at bat – initially a late, niche release for the Wii, and later ported to the 3DS where it suffered from the tiny screen. Xenoblade Chronicles X for Wii U didn’t fare much better, with most players missing out on the game. Third time lucky, then, for Xenoblade Chronicles 2, Monolith Soft’s epic new space fantasy. The trailer doesn’t reveal much, beyond it being an action-RPG, but it looks beautiful.

Splatoon 2

The first Splatoon was arguably the best game on the Wii U, so it’s incredibly good news to see Nintendo moving forwards on a full sequel for the Nintendo Switch – especially since the social nature of the portable console meshes perfectly with Splatoon’s multiplayer nature. It looks set to offer brand new ways to splat too, including more powerful weapons, new abilities, and arena-drenching inkstorms.

Mario Kart 8 Deluxe

Conversely, the Wii U’s other masterpiece is only upgraded for Nintendo Switch – but it seems to correct the original’s only grievous error. Battle Mode was a mess on the Wii U, and it thankfully looks to have been heavily refined here, bringing back more of an arena tournament rather than the track-based race combat of the base game. At the Nintendo Direct event on April 12, Nintendo added that the game will have more unlocked tracks, characters and carts than any previous version of the game. Deluxe arrives on April 28.

– Read WIRED’s Mario Kart 8 Deluxe review

Fire Emblem Warriors

Publisher Koei Tecmo doesn’t even need to show any gameplay in its reveal for Fire Emblem Warriors – the name alone reveals it’s yet another horde-based hack and slash effort, in the vein of Dynasty Warriors. However, the earlier Hyrule Warriors did an exceptional job of making the button mashing action blend seamlessly with Zelda lore, so hopefully this can do the same for the mythology of the Fire Emblem universe.

Arms

Nintendo isn’t much known for fighting games, but Arms looks like the Nintendo-est take on the genre you could imagine. Two fighters enter an arena and battle it out with extendable spring arms. Mechanically, it looks suited to showing off the functions of the dual Joy-Con controllers, with players holding one in each hand and using motion controls to attack and defend. During the recent Nintendo Direct event, the firm revealed more about Arms‘ gameplay, including a new character called MinMin, and said it will launch on June 16.

Project Octopath Traveller

It’s hard to parse much information from the 45-second reveal trailer, but despite surface appearances, this looks to be more than your standard retro-style JRPG. With deceptively attractive visuals – pixel-based characters inhabit a layered, 2.5D world filled with beautiful environments and impressive lighting effects – this seems set to dive into the minutiae of role-playing, teasing vastly different experiences based on your choices. Almost certainly not a final title either, but this an interesting-looking prospect from Square Enix.

Shin Megami Tensei: Brand New Title

The best thing about Atlus’ Shin Megami Tensei games is how mind-bendingly, gut-twistingly weird they all are. This cinematic trailer tells us nothing, other than the final game (probably) featuring some of the series’ more familiar demons, and a new hero – maybe? – who looks like a tokusatsu superhero, hanging out in a run-down building. What the game is actually about, we have no idea – but we can’t wait.

Sonic Mania

Sonic Mania is a loving flashback to the 2D superspeed side-scrollers of the ’90s. A celebration of Sonic’s origins and finest moments, the Nintendo Switch release doesn’t appear to be any different to the already-announced version for PS4, Xbox One, and PC, but it is nice to have confirmation it’ll be available – even if it is still a bit strange to see Sega mascot Sonic headlining a game on a console made by former rivals Nintendo.

Puyo Puyo Tetris

Sega dives deep into its catalogue for this puzzle game mash up. Tetris is an internationally renowned classic, while Puyo Puyo – beloved in Japan – is best known in the west as the source for Doctor Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine. This crossover was originally released for PS Vita and PS3 in 2014, but the Nintendo Switch release will be its western debut. The mechanics of both games are combined in various modes, to create an addictive new twist on fast-paced puzzle gaming. A slightly later release for the Nintendo Switch, this arrives on April 25.

Minecraft

Minecraft is set to join the Nintendo Switch ranks on May 11. The crafting game on Nintendo Switch will look similar to the Wii U version, complete with exclusive Super Mario Bros-themed content.

Ultra Street Fighter II

The game that dominated the fighting genre in the 1990s is making a return on Nintendo Switch with all the original fighters and bosses, the characters added in Super Street Fighter II, plus new additions Evil Ryu and Violent Ken. Players will be able to use Joy-Cons to challenge friends and strangers and, in addition to versus action, you can now team up with a friend to take on the CPU in Buddy Battle mode. The game is released on May 26.

And there’s more…

Following the Nintendo Switch’s reveal, other publishers started revealing their upcoming titles for Nintendo’s new machine.

Bandai Namco has confirmed Dragon Ball Xenoverse 2 will be coming to the console, while an entry in the Tales of RPG series is also in development. Most excitingly, the publisher is working on a new Taiko Drum Master release, bringing the brilliant rhythm action title out of Japan for the first time in years.

Activision has confirmed the enduringly popular Skylanders will be coming to Nintendo Switch, with the latest entry Imaginators arriving in March. The Nintendo Switch version will introduce a digital library, allowing players to store characters from the physical toys, making it easier to play on the go.

Ubisoft’s slate includes recent winter sports title Steep, taking players on a tour of the Alps; Just Dance 2017, now playable with up to six dancers at a time if you have multiple Joy-Con controllers (or use a smartphone app to double as one); and Rayman Legends: Definitive Edition, which the publisher calls the “ultimate version” of the beautifully animated platformer.

Classic indie games World of Goo, Little Inferno, and Human Resource Machine are heading to Nintendo Switch

Indie publisher Tomorrow Corporation has revealed it’s bolstering the day one line up with three games from its back catalogue. 2008’s phsyics puzzler World of Goo, 2012’s flammable mini-sandbox Little Inferno, and 2015’s programming puzzler-cum-corporate satire Human Resource Machine will all be available on the Nintendo Switch on March 3.

Interestingly, these will be digital-only releases, indicating Nintendo’s eShop – or the Nintendo Switch’s equivalent – will be active on launch day. Details on the online store have yet to be revealed by Nintendo though, and Tomorrow Corporation has not revealed prices for the trio of games.

Oceanhorn: Monster of Uncharted Seas, a Zelda-esque adventure has also been confirmed for release on the Nintendo Switch. Set in a water-logged world dotted with islands, players guide a young boy on a quest to find his missing father while uncovering the secrets of the ancient kingdom of Arcadia and a legendary sea monster – the Oceanhorn of the title.

Oceanhorn was first released on iOS in 2013 before receiving upgraded and expanded ports on PS4, Xbox One, and PC, so perhaps won’t be the most demanding of the Nintendo Switch’s power. However, the game’s publisher says it “will run beautifully on the powerful Nintendo Switch.”

No exact release date has been confirmed, but the game will launch in 2017. Perhaps more interestingly, the first game coming to the Nintendo Switch, albeit late, could be prelude to the in-development sequel Oceanhorn 2: Knights of the Lost Realm arriving on Nintendo’s hardware when development is finished.

Expect more games to be revealed for Nintendo Switch in the days ahead.

Nintendo Goes Indie

If the above slate of titles weren’t enough, Nintendo recently held one of its trademark Nintendo Direct broadcast exclusively focused on indie games.

The showcase unveiled a staggering 60 titles coming to Switch, showing a major push on Nintendo’s part to get more independent developers involved with the new console. It’s a great plan – indie devs are increasingly able to produce so-called ‘triple-A’ quality games, with an extraordinary amount of variety and imagination on offer. The independent sector is also showing tremendous growth – in volume of games and popularity with players – making it exactly the right creative community to court.

While some of the games announced are beloved classics – the likes of Towerfall: Ascension, The Escapists and Overcooked are perennial favourites that have already proven themselves – many will have enhanced features making use of the Switch’s unique hardware. Others, such as Yooka-Laylee and Gonner are brand new, and Nintendo has even managed to snag a few exclusives, as with Runner 3.

Release dates are still to be confirmed for many titles, but the full list of 60 indie games coming to Nintendo Switch is as follows:

- 1001 Spikes

- Away: Journey to the Unexpected

- Battle Chef Brigade

- Blaster MasterZero

- Cave Story

- Celeste

- Dandara

- Duck Game

- Fast RMX

- Flipping Death

- Gonner

- Graceful Explosion Machine

- Has-Been Heroes

- Hollow Knight

- Hover

- Human Resource Machine

- Ittle Dew 2

- Kingdom: Two Crowns

- Little Inferno

- Monster Boy And The Cursed Kingdom

- Mr. Shifty

- Mutant Mudds

- NBA Playgrounds

- NeuroVoider

- Oceanhorn: Monster of the Uncharted Seas

- Overcooked: Special Edition

- Pankapu

- Perception

- Portal Knights

- Redout

- Rime

- Rive

- Rocket Rumble

- Rogue Trooper Redux

- Runner3

- Shakedown Hawaii

- Shovel Knight: Specter of Torment

- Shovel Knight: Treasure Trove

- Snake Pass

- Space Dave!

- Splasher

- Stardew Valley

- State of Mind

- SteamWorld Dig 2

- sU and the Quest for Meaning

- Terraria

- The Binding of Isaac: Afterbirth †

- The Escapists 2

- The Fall Part 2: Unbound

- The Jackbox Party Pack 3

- The Next Penelope

- Thumper

- Toejam and Earl: Back in the Groove

- Towerfall Ascension

- Treasurenauts

- Tumbleseed

- Ultimate Chicken Horse

- Unbox: Newbies Adventure

- WarGroove

- WonderBoy: The Dragon’s Trap

- Yooka-Laylee

- Zombie Viking

1-2-Switch is Nintendo’s most innovative game in years, but there’s a catch

Milk a cow, make a baby go to sleep, strut, shoot, feel some balls, eat a giant sandwich… 1-2-Switch has got it all. While Zelda: Breath of the Wild is stealing the headlines, Nintendo’s curious mini-game collection is, arguably, a better demonstration of the Nintendo Switch hardware. And it’s great fun. For a bit. If you’re drunk.

There are 28 mini-games to get to grips with, nearly all of which are played by looking at your opponent, not the screen. The games have a feeling of WarioWare: Smooth Moves about them, but the cartoon characters have been replaced with human actors gyrating in brightly-coloured rooms. Nearly all the games require little explanation: in Shave you have to shave your face using the Joy-Con; in Ball Count you have to count the number of balls in the Joy-Con, a sensation ingeniously created using the controller’s HD rumble feature; in Wizard you have to battle your opponent by casting spells; in Dance Off, you dance.

As with WarioWare, the genius of 1-2-Switch is in the glorious incongruity of its mini-games. Staring into the eyes of a friend while miming milking a cow will always make you laugh. Then there’s Baby, where you’re tasked with putting a baby, apparently trapped in the Nintendo Switch’s portable screen, to sleep. Rock it in your arms and set it down on a flat surface just right to win. It’s odd. But it’s also very good. Table tennis, where you stand facing your opponent and thwack a virtual ball back and forth based on sound alone, is exceptionally fun. As is baseball, where pitcher and batter duke it out in a ninth-innings showdown.

Nearly all the games make use of the Nintendo Switch’s innovative hardware in one way or another. Eating Contest, where you have to chomp your way through as many virtual sandwiches as possible before the time runs out, uses the right Joy-Con’s infrared sensor to work out when your mouth opens and closes. The quicker you chomp, the faster you get through the pile of sandwiches. But where Nintendo takes this kind of innovation next will be the real test of the hardware.

Most people will get a couple of hours of fun out of 1-2-Switch, but that’s it. Then, like so many party games, it will sit gathering dust until you’ve next got a house full of people, a bottle full of gin and a fridge full of tonic. This is an excellent party game and one quite unlike any that has come before.

Yet the game’s biggest fault is more to do with how it’s sold. For all Nintendo’s protestations, 1-2-Switch absolutely should have been bundled with the Nintendo Switch. It’s an excellent demonstration of the hardware and the sort of game that could be chucked on when you’ve got friends over and want to show them what the console is all about. Instead, you’ll have to fork out £35 for a limited, albeit fun, tech demo.

1-2-Switch is Nintendo’s most innovative game in years, but there’s a catch

Ubisoft is using AI to catch bugs in games before devs make them

AI has a new task: helping to keep the bugs out of video games.

At the recent Ubisoft Developer Conference in Montreal, the French gaming company unveiled a new AI assistant for its developers. Dubbed Commit Assistant, the goal of the AI system is to catch bugs before they’re ever committed into code, saving developers time and reducing the number of flaws that make it into a game before release.

“I think like many good ideas, it’s like ‘how come we didn’t think about that before?’,” says Yves Jacquier, who heads up La Forge, Ubisoft’s R&D division in Montreal. His department partners with local universities including McGill and Concordia to collaborate on research intended to advance the field of artificial intelligence as a whole, not just within the industry.

La Forge fed Commit Assistant with roughly ten years’ worth of code from across Ubisoft’s software library, allowing it to learn where mistakes have historically been made, reference any corrections that were applied, and predict when a coder may be about to write a similar bug. “It’s all about comparing the lines of code we’ve created in the past, the bugs that were created in them, and the bugs that were corrected, and finding a way to make links [between them] to provide us with a super-AI for programmers,” explains Jacquier.

Ubisoft hopes that Commit Assistant will cut down on one of the most expensive and labour-intensive aspects of game design. The company says that eliminating bugs during the development phase requires massive teams and can absorb as much as 70 per cent of costs. But offloading the bug-killing process to AI, even partially, isn’t without its own challenges. “You need a tremendous amount of data, but also a tremendous amount of power to crunch the data and all the mathematical methods,” he says. “That [allows] the AI to make that prediction with enough accuracy so that the developer trusts the recommendation.”

It’s still early days – Ubisoft is “only starting to pollinate” Commit Assistant to its development teams and, so far, there’s no usage data on how much it’s impacting game creation. There’s also the human factor to account for: Will developers want an AI poking through their code and effectively saying “you’re doing it wrong”?

“The most important part, in terms of change management, is just to make sure that you take people on board to show them that you’re totally transparent with what you’re doing with AI – what it can do, the way you get the data,” says Jacquier. “The fact that when you show a programmer statistics that say ‘hey, apparently you’re making a bug!’, you want him or her [to realise] that it’s a tool to help and go faster. The way we envisage AI for such systems is really an enabler. If you don’t want to use that, fine, don’t use it. It’s just another tool.”

Yves Jacquier heads up La Forge, Ubisoft’s R&D department

Ubisoft is working on other AI applications beyond Commit Assistant, though Jacquier emphasises that it is only currently useful in dealing with very specific individual tasks – like getting virtual agents to avoid walking into each other. “AI so far is very good at making decisions on very narrow topics, like Alpha Go,” he says. (AlphaGo is the AI system from DeepMind that beat top Go player Ke Jie at the notoriously complex board game in May 2017.)

“We’ll see in the future more and more examples where this works, but in reality, [something like] a self-driving car, you won’t see in our streets probably until 20 years from now,” he says. “Simply because all those self-driving cars would have to avoid other automated vehicles, pedestrians, old-school cars driven by real humans, and rogue factors like wildlife wandering onto roads.”

But improving AI in gaming could help solve some of these real-world problems. Olivier Delalleau, an AI programmer at Ubisoft, spoke at UDC about autonomous driving in Watch Dogs 2. Using an example of a non-player-controlled car driving around the game’s virtual San Francisco, Delalleau showed how, initially, it would more often careen out of control when taking corners. The car was programmed with the goal of reaching a destination or looping the streets, providing visual flavour to the game world.

Ubisoft taught cars in Watch Dogs 2 how to brake and take corners

“[We found] cars never braked, because they didn’t find it was a good solution,” Delalleau says. As a result, it didn’t learn to brake. “It’s pretty difficult [for an AI] to learn to brake, because it [doesn’t see it as] a good solution most of the time. You need to help it find that it is a good solution.”

Delalleau used reinforcement learning, a form of machine learning, to help the AI learn this skill. Ubisoft provided thousands of examples of braking when driving, and the system learned that it could achieve its goals more efficiently by following the rules of the digital road. The outcome was that the AI cars began taking corners more slowly. This made Watch Dogs 2’s representation of San Francisco more realistic and reduced random crashes.

Jacquier believes that similar work could help inform AI systems with real-world applications, such as driverless cars. “In terms of ethics, I think that actually the games industry can help,” Jacquier says. “When you’re wondering how an autonomous car will behave in a situation that involves pedestrians or other cars, it’s like the Trolley Problem. That’s something you wouldn’t be able to test in real life, either for moral reasons or cost in some situations. But maybe you can have some fair answers by simulating that in a video game environment, and see how your AI would behave.”

Enemies in Far Cry 5 will look to save themselves according to a hierarchy of needs

Other areas in which Ubisoft is using AI include non-player characters (NPCs). In the upcoming Far Cry 5, Ubisoft has implemented a virtualised version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs – the psychological theory of motivating factors for human behaviour – for NPC characters. This gives in-game agents motivations for their actions, and is modeled largely on the self-preservation strata of Maslow’s pyramid.

When a player encounters a non-player character in Far Cry 5, two systems are at work: trust and morale. If you raise your weapon at someone you’ve never met before, they will react with distrust or fear, warning you to lower your gun. If the NPC recognises a lingering threat from you, it will launch an attack of its own, fearing for its own ‘life’. When facing a group of enemies, as you pick off members of a gang, individual foes may realise they’re outclassed and lose their thirst for combat, and attempt to flee as they sees their ‘friends’ taken out. Elsewhere, animal companions will respond to player activity, cowing close to the ground unprompted when you crouch into stealth, for instance. It’s the sort of work that adds depth and realism to the world.

In future, tools such as Commit Assistant could spread beyond the confines of Ubisoft. La Forge developed the AI in conjunction with the University of Concordia and published academic papers on how it works. “If someone else wants to implement this kind of method, it’s totally possible to do that by getting those articles, which are public,” says Jacquier.

The system wouldn’t be of use to all developers though. It very much thrives in a ‘big data’ environment with near countless examples of what not to do to feed it as a guide. That restriction, for now, renders it uniquely beneficial to big-budget studios.

But if Ubisoft’s artificial baby matures as is expected, the pay-off for players could be significant – it could mean fewer release dates are pushed back for bug fixes and fewer bugs end up in the finished product. Meanwhile, it could free developers to focus their attentions on improving other aspects of the game. Perhaps best of all, if everything goes according to plan, you’ll never even notice.

Ubisoft is using AI to catch bugs in games before devs make them

Spawn as another player’s baby in survival game One Hour One Life

I’d grown to be a young woman, the last in my tribe, tasked with running to the ponds for water to keep our crops alive. I’d just returned from one of these long errands when my ageing mother took me aside to tell me that only by raising my children could we ensure the tribe’s future.

Just then, I spawned my first child. Unfortunately, I was carrying no food, and the hunger that had gnawed at me as we spoke was to be my undoing: as I picked up my child to nurse them for the first time, the extra energy expenditure tipped me over the edge of starvation. Within seconds, I was dead. I only hope that my mother was somehow able to save my daughter.

Developer Jason Rohrer, known for experimental and art games including Passage, The Castle Doctrine and Chain World, calls One Hour One Life his “love letter to human civilization”. Aptly described as “a multiplayer game of parenting and civilization building”, it may be his least abstract and most approachable game to date.

In the game, you start life as the helpless infant of another player, entirely dependent on them to nurse and care for you. Over the next few minutes, you’ll grow into a weak but independent child, able to help your community. With luck and cooperation, you’ll survive to have children of your own, becoming one link in a generational chain.

The game world on the server is persistent, but your character and their life are unique. Every time you die and respawn, you do so as an entirely new, randomly-generated person. You can communicate with other players via a text box, which allows you to type just one or two characters when you’re a baby, before expanding to allow full, if brusque, sentences as you grow to adulthood.

One Hour One Life‘s difficulty curve can be punishing on an emotional level as well as a technical one. But it’s also rewarding – I felt genuine pride when I learned where to find fertile soil to plant our fields or how to crush a gooseberry with a flint chip to produce a seed that would, in time, give us a bush to provide dozens of berries.

The importance of cooperation and mutual aid in the game rapidly becomes apparent. Although there are built-in tips on what you can do with any given object, it is other players who provide the hands-on lessons in survival. It’s only because of my fellow players that I learned that sitting by a fire would dramatically reduce my energy expenditure; that dying brown fruit bushes could be restored with water, and that leaving one row of carrots to flower produces seed for the next planting.

Solo foraging can keep you alive for a while, but to establish a safe home and food supply for yourself and your descendants, you’ll need to farm, build and hunt, and that requires more than one pair of hands.

Women are uniquely important in One Hour One Life, as only women – without the involvement of any men – can have children. This design choice is a reflection of the Rohrer’s own views. “Every woman in the world is at the end of a chain of women who had at least one daughter, going back for 400 million years like endlessly nesting matryoshka dolls,” he says. “Women are the branches of the human family tree, where men are just the leaves.”

In One Hour One Life, the disproportionate importance of women, and thus female children, in sustaining your tribe through multiple generations leads to its own emergent gameplay. When times are hard, it’s not uncommon for male babies in particular to be rejected and left to starve by a mother who has only enough food resources to sustain one, while more sentimental players may struggle and die in a vain attempt to keep multiple offspring alive against all odds.

If you live past infancy, the game can be easier to play if you spawn as a male child. Once weaned, you can survive on your own and try to learn and help your community as best you can, but your mistakes are less likely to result in someone else’s death than if you were a woman. But, as Rohrer points out: “As a male character in this game, you feel your lack of importance acutely. If you wander off into the woods, you can live out the rest of your life, but you will do it absolutely alone, with no means of bringing other players into the game to join you.”

If the game’s design and mechanics lend themselves to matriarchies, they are also arguably rather bioessentialist (although not heteronormative – the most common family structure I’ve seen while playing the game has been centred around two or more women). Although the ability to spawn new players is unique to female-coded characters, Rohrer says that gender-coded behaviours, clothing and performance aren’t linked to sexual attributes. “There are two biological sexes in the game, but there are as many genders as people want to play,” he says. “After all, in this game, you are often tasked with playing a character who does not match the gender you identify with in real life.”

Not all women will be fertile, either: “It all depends on the flow of players into the game, and the way the child placement algorithms shake out.” However, he emphasises, “this is not a game about player customization. It’s about playing a character in a unique situation in each and every life.”

One Hour One Life is free and open source, but the game is primarily played on Rohrer’s own game server, for which you’ll have to pay $20 to get lifetime server access and support. When you sign up, you’re sent a unique login key, along with a download link to clients for Windows, macOS and Linux, plus the full source code and Linux server source code that you’ll need if you want to run your own private game server.

The game and its community are at times reminiscent of the early days of Minecraft, sharing tips, support and discussion on the official forums, a crafting recipe wiki and a review board, where players have taken to telling their characters’ stories.

The game can be tough, particularly while you’re learning your way around, and especially if earlier players have pillaged the resources of the area you spawn in. Childhood is difficult to survive and, if you’re an Eve – a reproductively mature woman spawned ex nihilo to balance user numbers – you’re at the mercy of both the environment and the needs of your potential brood of offspring.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its challenges, One Hour One Life‘s gameplay keeps dragging you back, while characters’ limited lifespans lend themselves to casual play.

All survival games are ultimately about forging your own story, but the interdependent community aspect of One Hour One Life means that the stories you create are intimate, complex and multidimensional in ways that few other games approach. Here, the pain of losing a family member and the joy of raising a child to adulthood are recreated in a moving microcosm of the human condition.

Spawn as another player’s baby in survival game One Hour One Life