As the blocky exploration game and creativity tool reaches its first decade, our games writer – and the father of someone on the autism spectrum – reflects on the impact it has had

Hidden away somewhere in my attic is an old Xbox 360 that I’ll never throw away. On its hard drive is a Minecraft save file that contains the first house my oldest son ever built in the game. He was seven and, coming from a boy on the autism spectrum with a limited vocabulary and no patience to draw and paint, his creation was a revelation. Sure, it is a monstrous carbuncle, a mess of wooden planks, cobblestone and dirt. But it is also the greatest building I ever saw.

Now Minecraft is 10. The building-and-exploring game, originally developed by one coder, Markus Persson, in his spare time, has now sold 176m copies across 21 platforms. A free-to-play version launched in China via a partnership with NetEase has been downloaded 200m times alone. Every month, 90 million people around the world play Minecraft. There are Minecraft clothes, Lego sets and spin-off games. In spring 2022, there will be a live-action Minecraft movie.

But this isn’t just a story about sales. “Minecraft is personal,” says Lydia Winters, the brand director at Mojang, the Swedish studio behind the game. “It has become part of players’ identities.” Lydia started out as a Minecraft YouTuber, making videos about the game during a tough time in her life. Her marriage had ended, she’d moved homes, she was a little bit adrift. “There is such a community feel to Minecraft. I would jump into a game with another player that I’d met online and we’d just see where the day took us. We’d hop on a server and we’d run. Every experience was unique and individual, [filled with] the limitless potential of what we could do together. It was huge for me.”

There are lots of ways in which the game has had a profound influence. Early on, Persson made the decision to release the game in an unfinished “alpha” state, so people could try it and give him feedback. He charged for the download but made it clear that anyone who bought it would get the finished version for free. Very quickly, thousands were playing, and the money allowed him to leave his job, set up Mojang and employ a team, while the feedback let them create a better game.

In this way, Minecraft effectively invented the “early access” model that a huge number of independent game developers have now embraced, to take some of the uncertainty out of development. Rather than working for two years on an offbeat game, then releasing it and crossing their fingers, studios will now get it out there as soon as possible, charging players to become part of a sort of extended developer community. Minecraft changed the whole structure and economic model of the games industry.

It also changed the structure of the gaming experience. You don’t win or lose in Minecraft. It presents you with a blocky world that you are free to explore. You chop down trees and make a house, you mine for materials, you can make a sword and fight zombies, but the fun – the reward structure – is all extrinsic: it’s about exploring your own creativity, making your own rules, hanging out. There were other open-ended simulation games around – The Sims, of course, but also closer influences on Persson, such as Infiniminer. But there was something about Minecraft – perhaps its quaint visuals, its mix of exploration and creativity, its cooperative multiplayer functionality – that made it special. That made it personal.

Minecraft also became a focus of the emerging YouTuber community. The concept of the Let’s Play video, wherein fans filmed themselves playing a game then shared it online, was in its infancy in the early 2010s, and many latched on to Minecraft as the perfect subject matter, thanks to its inherent humour, its funny, blocky creatures and its open-ended structure. YouTube gamers and presenters had a huge amount of room to express themselves and explore idiosyncratic ideas in the game. Some of the biggest YouTubers in the world, such as StampyCat, Amy Lee and DanTDM, built their millions-strong fanbases by messing about in Minecraft.Advertisement

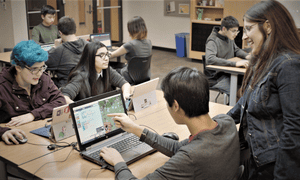

There are other important contributions the game has made over the last decade. Early on, Persson and Mojang took a relaxed approach to their code, allowing fans to modify the graphics and rulesets and then distribute their versions across the globe. In 2015, Mojang partnered with the Hour of Code campaign designed to get children into programming, and the company created a Minecraft Hour of Code tutorial to teach fans of the game some basic elements of coding. Through Minecraft Education Edition, hundreds of schools around the world now use the game to teach everything from physics to theatre studies, proving that video games have a place in the classroom.

Most crucial for me, personally, is the social aspect. Although you can play little competitive Minecraft minigames, the main experience is collaborative. You can enter a world with a group of friends and build and explore together. For a lot of children – especially non-neurotypical children, or the shy or awkward or lonely – it has been a godsend; a way to make meaningful friendships without having to cope with or understand a lot of the intricacies of physical contact.

How valuable is this? Where do I even begin? Having written a novel in which Minecraft is a major component, I have spent the last two years talking at festivals, conferences, bookshops and libraries about autism and Minecraft and the power of video games. Whenever I speak, I end up chatting to people afterwards and, invariably, somewhere in the little queue, I’ll spot a parent standing beside a slightly shy child, and they will both look kind of worried or hesitant, not knowing quite what to say.

But then they’ll tell me their story. Their son or daughter barely spoke, struggled at school, had no friends – and, oh god, I saw the worry of that, the worry and sorrow of it, every time in the way they spoke to me. But then their kid started playing Minecraft. Often that’s a concern at the start, because the parents aren’t always gamers, but the next thing everyone knows is that the kid has friends, they’re building Hogwarts together, they’re chatting, they’re confident. They have ideas and plans. I’ve heard it dozens of times, all over the world, from Brussels to Dubai, and it never gets old: this game changed our lives.

Sitting there nodding and smiling in agreement, I sometimes struggle to hold it together. Because in the back of my mind is that old Xbox 360 in the attic, and what lives on it, and what it means. The house my kid built when we weren’t sure he’d ever draw or paint or make anything, and the goddamn sunlight of that, the beauty of it. The relief.

So forget the sales figures, forget the revolutionary industry practices, forget the “brand extensions”. Ten years of Minecraft has been 10 years of people finding a place to be creative, expressive and social, somewhere they feel safe and welcome, and 10 years of parents like me looking on, holding themselves together, thinking, at last. At last.